The first reports of a mysterious and devastating illness made their way to Champaign-Urbana in 1981. It impacted gay men in particular, with fever, muscle pain, night sweats and other symptoms, then skin lesions, pneumonia, and a certain cruel death. Unnamed and untreatable, “gay cancer” or the “gay plague” spread tendrils of fear into the local community. Through the 1980s, it was a death sentence without question. Almost as harmful was the “social death” that impacted gay men, both sick and well.

In 1983, the first case turned up at a Champaign hospital. A Bloomington man, afraid of being identified as gay in his hometown, sought help here. Then it hit a University of Illinois professor of Chinese history, and then a much loved local hairdresser. Soon Champaign-Urbana had its own epidemic.

Pictured left to right: Julie Pryde, Joan Lathrap, Jerry Carden. Photos by Cope Cumpston.

Pictured left to right: Julie Pryde, Joan Lathrap, Jerry Carden. Photos by Cope Cumpston.

A health educator at Burnham Hospital took particular alarm; he was a gay man. Jerry Carden feared for his life, and for the entire gay community. He made it his business to learn as much as he could, and strategize about what needed to be done. Without internet back then, information was difficult to uncover and often misleading. Even as late as 1985 there was little medical knowledge of what the disease was and how it spread. The stigma against gay men became virulent and ugly; people were afraid to simply shake hands, and far more. In September 1985, a small group gathered at McKinley Foundation to decide what was most needed; out of that came GCAP, the Gay Community AIDS Project. Its first urgent goals were accurate information, outreach and education, and support as needed. A well-known Chicago journalist, Rex Wochner, “a one man gay Associated Press,” wrote the articles of incorporation. Carden was founding chair.

Joan Lathrap arrived in Champaign/Urbana from Bucks County, Pennsylvania, a place steeped in the arts and associated gay culture. Active in community theater, she appreciated the richness of the gay community.

Trained as a social worker, Lathrap became the first one on staff for CUPHD, the Champaign-Urbana Public Health Department, in 1976. She took full advantage of an open job description to develop programs where she saw need. When the AIDS crisis took hold locally, she used her powerful networking skills to reach into the impacted community. She was quick to become active with visiting nurses and GCAP. Soon the Illinois Department of Public Health (IDPH), arrived in Champaign with a centrifuge, the best tool then for blood analysis and diagnosis, and told her to get to work. She already had.

At that time the best sources of information were on the coasts: New York and San Francisco. The Gay Men’s Health Crisis in New York was a strong center. Carden and Lathrap reached out for up-to-date information about the disease, particularly guides to safe sex. One angel with the IDPH was Carol Gibson, who would arrive in Champaign-Urbana with a car full of handouts and the latest medical information. GCAP used these and put together their own wallet-sized leaflets to leave, with condoms, in strategic places. In those days there was a local network of tea rooms where gay men gathered; many of them closeted, often married, sometimes prominent men hiding their sexuality. The bowling alley in the Illini Union was known, along with a few key bathrooms in the Illini Union and other places. In the 80s there were a number of active gay bars where the community gathered, notably Chester Street, Balloon Saloon, and Giovanni’s, which burned down early on. The pamphlets from San Francisco and NYC used street language for body parts and sex acts, and were angrily opposed by Tim Johnson, then a state representative, who tried to cut any state funding for GCAP.

Another danger was that people early on were warned not to have their blood tested, or risk being outed. Private clinics did not promise anonymity; CUPHD did. Lathrap remembers the early primitive lab for blood testing, with no special equipment and high backless chairs. Young men would come in terrified and nearly fall off the stools; one nurse had a Mickey Mouse watch that she used to calm them down.

Lathrap realized that local men who had moved away and then been diagnosed were coming home to die. Sometimes their families weren’t willing to help. There was an acute need for housing and other support, even money for bus tickets, which Travelers Aid provided. And still, caretakers were afraid to have direct contact with an AIDS sufferer. They would leave food outside doors and keep as physically distant as possible. Schools entered the ranks of uncertainty; teachers were reluctant to touch children after playground incidents, for fear of blood contamination.

In 1995 protease inhibitors were introduced that provided effective treatment for AIDS, and today with medication people who are HIV positive can live normal lives. But in the 80s, only three local doctors were willing to see AIDS patients.

CUPHD created Outpost, a gay community center, then Outzone, centered on young people. Lathrap remembers that teens with braces wanted to know whether they could get AIDS from French kissing. Further outreach became necessary as AIDS spread to women and into the African-American community.

One day in 1988, a leather-jacketed, spike haired, outspoken grad student named Julie Pryde walked into Lathrap’s office and asked what she could do. Pryde had arrived in C-U from Maroa, the small town near Decatur where she had come out, and was alarmed by friends getting sick and dying. She came to the U of I to learn what she could to make an impact. First she approached the Psychology Department; they sent her to Social Work, where she got a degree, and then found her way to Lathrap’s office at CUPHD. The two were clearly kindred spirits; Lathrap says it took her about ten seconds to point Pryde to a chair, hand her a pencil, and put her to work. She did whatever was needed. Part of her beat was to drive up to Chicago to buy all the gay newspapers for up-to-date information. The Little Professor Bookstore in C-U was another good source.

While interning for Lathrap, Pryde was beaten down by dismissive and judgmental encounters among the leaders in town, police, fire departments, and EMS workers among them. When she lost three close friends, it all became too much and she left. But in 1995 Lathrap called to tell her of an open position at CUPHD. Pryde began as advocate, mentor, and researcher, going deep into the community where the need was. She remembers doing blood tests out of her car. When Lathrap retired in 2000, Pryde became Director of Social Service, then Director of the HIV Division, and in 2007, overall administrator.

Photo by Kwamé Thomas

Recently, the state of Illinois adopted a program to eradicate new cases of AIDS by 2030, Getting to Zero, with CUPHD helping to lead the charge. Our community has been a center of the action since the beginning; thanks to determined work by Lathrap, Pryde, and Carden among many others, C-U has long been recognized as a leader in innovative and progressive action against HIV/AIDS. Now, its impact is greatest outside the gay community. In 1996 despite some controversy, GCAP changed the first word of its name from “Gay” to “Greater” to reflect the broader scope of people affected by HIV/AIDS. Mike Benner continues its work today.

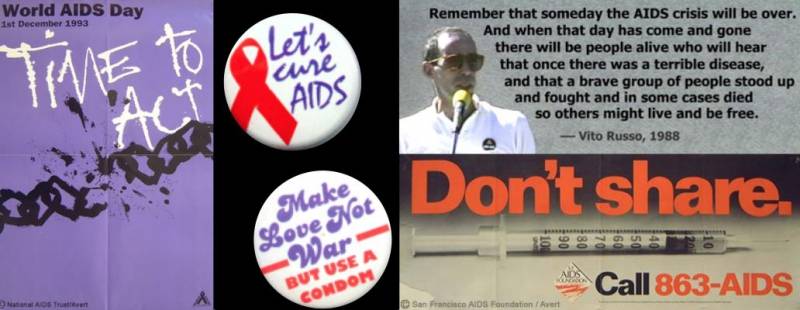

Though immense progress has been made, the tragedies of HIV/AIDS close to home and throughout the world have not ended. On December 1st, take a moment to honor the pioneering work of Lathrap, Pryde, Carden, and the others who made C-U a center of activism in the 80s and continue the fight today. There’s still work to be done.

On December 2nd visit Krannert Art Museum for the 30th annual Day Without Art, founded to note the many artists felled by AIDS. In collaboration with Visual AIDS, KAM will host a series of seven films commissioned to respond to the continuing issues.

You can find more information about the work CUPHD is doing with HIV and AIDS prevention on their website.