“And, when the winged gods finally interfere / with your possessor’s enjoyment, to an / indefinite extent, I’ll remember a time when / men were the ones doing harm with / their own hands. I’ll remember the words I once / had to give to you, on the porch, in private.” The narrative arc within these words alone from the title poem of Love Letter to Who Owns the Heavens perfectly embodies the breadth of moving yet interconnected parts and expanse of vulnerability present within each page. From the evocation of gods, growing technology, and the grounding of our own history to the closeness and transformation of love over time, author Corey Van Landingham invites us to wrestle with and even redefine our relationship with intimacy.

With Love Letter to Who Owns the Heavens being Van Landingham’s second book of poetry, she showcases not only her ability to build off topics she has previously explored but also her aptitude for making such encompassing aspects of our world feel like they are within our personal atmosphere. Certainly, the topics that Van Landingham addresses are not new ones, but her unique take on focusing on the interconnectedness of these overarching topics beckons us to consider our own connection to everything we know and love. Recently, I had the opportunity and pleasure of interviewing her and gaining more insight behind the force that is Love Letter to Who Owns the Heavens.

Smile Politely: What was your earliest memory of writing? What made you fall in love with writing in the first place?

Corey Van Landingham: My first memory associated with poetry is super corny and precious, but the first poem I ever wrote was before I could write. I walked into the kitchen and said, “Mom, I need to write a poem.” She had to go get a pen and paper, and I dictated to her this poem. It has cats sleeping with their mother in the barn, and then there’s like unicorns in it. When I look back to it, it does have the rhythm of a poem, which is strange from a three-year-old but maybe not that strange because my mom read poetry to me all the time. Whenever my friends have children, I get them this anthology called Silver Pennies, and it’s poems for children, but it’s real, serious poets in this anthology with poems that are fairly magical, that have refrain, really musical, and so she was reading stuff to me from that all the time.

SP: What writers have influenced your style of writing specifically? What writers do you specifically look up to?

Van Landingham: The poet who first gave me permission to both have the music I wanted in the poems and this attention to the exquisite detail but also to have this kind of macro-level of thinking was Linda Gregerson. Her poems are often braided. She brings in different threads and strands. There’s science, politics, and art. She writes a lot about theatre as well as personal narrative, so when I first read her poems, something kind of exploded in my head, the fact that you could do everything all at once. You don’t have to sacrifice sound or image to write poems that are about these larger, pressing political issues, which, you know, everything — every poem — is political in some way, and that was really thrilling to me, to get that kind of permission. In terms of writers I look up to — Lucy Brock-Broido was a poet that was really important to me as well and her writing of persona poems. She would inflect the voices of other people with her own idiosyncratic, strange, surreal lushness.

SP: How would you personally define poetry, your own poetic style, and even what poetry means to you?

Van Landingham: Poetry can be almost anything. For me, poetry is about attention and layers of meaning in compressed — though compressed could be debated — attention to language. That part of attention is important because it can be attention to a lot of different things — attention to how language is made, exquisite attention to the image. It can be attention to the exterior world. It can be attention to the internal self. It can be all the above, so that’s the most important thing that marks the poetry I most admire.

As far as my own style, I revise it from book to book. I get really restless, and I don’t like to repeat things all that much, although I repeat subjects. After my first book, I was like “I’m never going to write another elegy for my father. I’m never going to write another love poem.” Well, this whole book is full of love poems and has elegies for my father, and so does my third book! And we’re haunted by our obsessions, right? But I want to approach each of them from a different vantage point, a different perspective because I’m not the same person I was when I wrote my first book. I’m not the same person I was when I wrote this book even, so that’s something I always just want to change.

As far as what poetry means to me, I just tie that back to attention. We have so many things that demand our attention, and it’s so easy to walk around and experience the world where you’re looking at everything but also nothing at the same time, so there’s necessity to slow down, to pick this word — the exact right word, to see something and think, “That’s a poem because I don’t know everything about that yet, but I want to figure something out on the page,” which is, of course, more than just on the page.

SP: From a future materialized in the present through drones and other technological forms to exploring what the past holds and how it has influenced us alongside challenging the very definitions of intimacy — why these themes? When was the moment you decided, “I need to write about these”?

Van Landingham: The book started to come together when I moved to the Bay Area in the fall of 2013 right before my first book was coming out, so I was going to workshop at Stanford. Almost anywhere you are on that campus, you can see the Hoover Tower, which hovers over everything and is part of the Hoover Institute where Condoleezza Rice teaches. Literally, the Library of War is situated there, and it kind of hovers around you wherever you are, so that was part of it. Then also, the campus is right next to the Facebook campus. Google buses would be passing you all the time, so there’s a booming tech industry that was inescapable as well. Both of those things invited poems that are thinking about distance, proximity, and technology, how technologies become an abstract proxy for the body, and how that informs various relationships, whether it’s personal relationships — I was in a long-distance relationship at the time, our relationships to violence from afar, and relationships to various figures of power, whether they’re personal or political, fathers or presidents or gods or something like that.

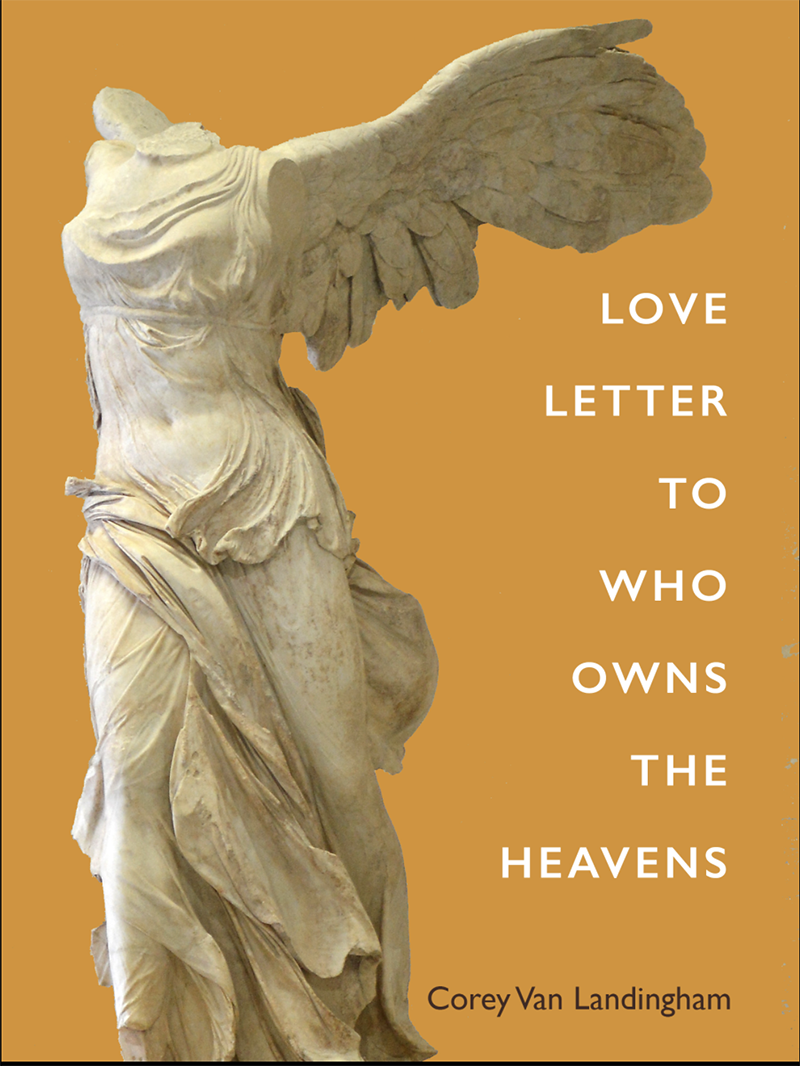

Photo from Tupelo Press website.

An image of Van Landingham’s book Love Letter to Who Owns the Heavens. The cover is orange, and the title text is white and justified to the right. An image of the sculpture titled “Winged Victory of Samothrace” from the Louvre Museum is to the left of the title text.

SP: How did you decide on love and intimacy being through lines for the rest of the themes and the book itself?

Van Landingham: I was reading a lot of letters. To me, what’s so thrilling about the epistolary form of the poem that acts as a love letter is that you have one foot that is stepping into the quotidian world, this expression of the self that is supposed to seem somewhat dashed off and authentic, this kind of intimacy of reaching across a distance, but then there’s also this artificial part of it that, you know, if you’re writing a good letter, you’re putting some art into it at the same time, but you’re not trying too hard to seem artful. That feels like an apt kind of metaphor for me and poetry but also just how we communicate feelings of love and especially in a love poem that, you know, you want to seem intimate and tender perhaps or maybe enraged, vitriolic — who knows? But you want it to feel sincere without sacrificing that kind of clay and attention of language, so the love letter allowed me to think about that in these poems as well as that crossing of a distance, the presentation of the self that comes from solitude, and what does it mean to try to write to someone who you can’t see, who you can’t touch.

SP: How were you able to select such specific instances in history to further what you wanted to say? How was the research process?

Van Landingham: It’s one of my favorite things about writing poetry, these strange wormholes that you go through or the rabbit holes, and you’re just going to get sucked down into something so strange. It’s about knowing that there are layers to be uncovered, and that’s why I go to a poem, not because I already know what I want to say but because I want to figure something out. You have to find the exact right thing that kind of acts as a portal, and that’s what is the exciting thing about lyric poetry. You can have all these collapses, collapses of time where imagining the future, experiencing the present, and dipping into the past can all be collapsed into three lines. That’s thrilling to me because when you feel the past close to you, you can understand your position in the world a little bit more and allow you to imagine yourself into the future.

SP: In this book, the father “was a slow kind / of shattering” as described in “King of Hearts,” “turned into ash so he could never be resurrected’ in “Elegy.” Could you speak more to the story behind this father, his complex nature, and what he represents in this specific book?

Van Landingham: I like thinking about him in the context of this specific book because my first book does approach the father figure a lot too. I think in that book, I was a lot closer to my father’s death. It was published only five years after he died, so I had a lot more distance in this book. I think I return to him in some way because I do think that the longing of the elegy — to keep the dead close to us — is one that speaks to the kind of impossible intimacy of the lyric poem. We can’t keep the dead with us literally, but we can metaphysically perhaps, and figuring them in art is one way to do that. To me, that has a lot to say too about how we experience love in general and especially a long-distance relationship of having to build someone up in your mind and your imagination — to imagine that they’re with you in some way even if they aren’t.

SP: Were there any poems in the collection that really stood out to you as you were writing Love Letter to Who Owns the Heavens?

Van Landingham: The easy answer might be one of the last poems I wrote for this just because I feel the closest to that aesthetically, personally, and that was “The Eye of God.” It was a poem that helped me connect a lot more of what the book was trying to do in terms of — you know, I was talking about the collapses of the lyric poem before and thinking about this kind of omniscience, and in the epigraph from Gregoire Chamayou, what she’s talking about is the drone operator’s ability to see before a drone strike, to experience the drone strike from afar, to see it afterwards, and to see it from multiple perspectives and vantage points too, so that’s what’s being thought about as the eye of God, and I didn’t want to draw any neat parallels, but to me, that’s lyric poetry at the same time — seeing and bringing the past, the present, the future altogether into one moment.

Learn more about Corey Van Landingham on her website, Amazon author page, or follow her on Instagram.