Editors’ note: This article was originally published on Wednesday, April 14th, but was removed after a series of concerns were expressed by a member of C-U’s LGBTQ+ community. After careful consideration on the part of the writer and Smile Politely’s editors, we have decided to republish the article in its entirety. We value the fact that our publication encourages debate, and we stand behind the thoughtful words of this writer who has the right to interpret and frame their experiences in their own words. We also support and respect this queer writer’s belief that everyone in the LGBTQ+ community has different experiences and perspectives, and that this article only underscores the diversity of C-U’s LGBTQ+ community.

Setting foot inside the 2021 MFA Exhibition was like stepping through a portal. Each installation created its own reality, giving me as much breath as my presence was giving it newfound purpose.

There is just so much power in filling an empty space exactly the way you want to. Allowing other people to then explore that outward expression of you? Well, that is bravery. And it is an honor to interact with what these artists have decided to share about themselves and how they see the world. This experience becomes intimate when we dig deep enough for the identities embedded in the art to speak louder than the warped images others have projected onto them for us. For LGBTQ+ artists, both the social risks and emotional benefits of sharing aspects of their identities in their work are particularly high.

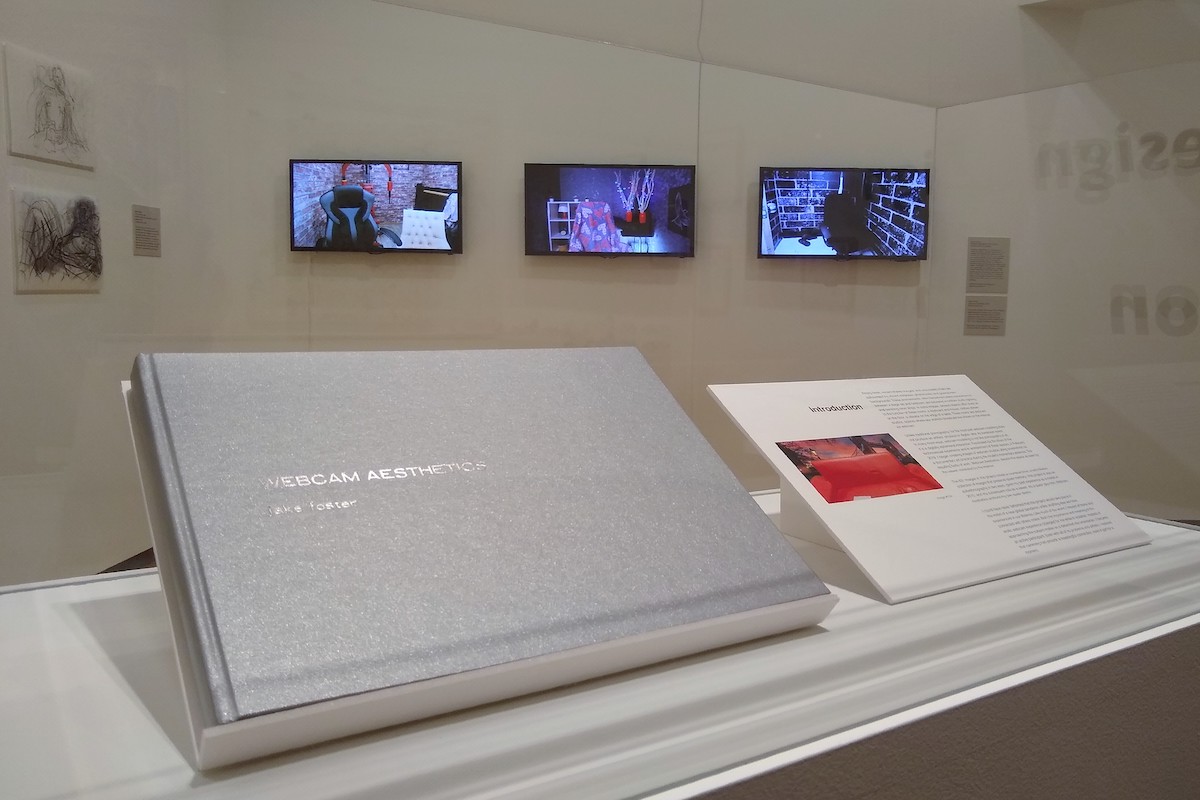

Before any sharing can take place, an artist must build up a concept from the inside out. MFA graduate Jake Foster knows this more than most. His installation, ‘Webcam Aesthetics,’ depicts various interpretations and expressions of queer webcamming both before and during the age of COVID-19.

“Since I came here, I’ve investigated new themes,” he says, referencing his evolving artistic style. “I kind of had that freedom that I didn’t have when I was living at home and around family in New Jersey to investigate these super weird and queer subject matters that I am so interested in now.”

Photo courtesy of Jake Foster.

There is an inevitable element of self-discovery in that exploration, one that amplifies during a time when disease is limiting our ability to do so outside of ourselves. “At one point after I started the project, I considered stopping doing the project and moving on to other projects,” Foster admits. “And for maybe several months during the beginning of it I couldn’t make anything at all. I was just kind of shocked.”

That shock didn’t slow him down for long, though. “Especially when [COVID-19] started happening it kind of gained new importance,” he says. “I had family back at home in New Jersey that was experiencing the COVID lockdown quite differently than we were. And the rates were much higher, like in the New York City area. Yeah, it was really stressful during that time. So I think all that kind of came out in my work.”

Olly Greer, another graduating MFA student, has funneled more pre-pandemic memories into their final installation entitled ‘Dykesthetics.’

“When I came [to the University of Illinois] and saw what the frats were, I was retriggered,” they say. “I was brought back to being a 16 year old… lying about my age, lying to my mom. We would lie and say we’re standing at each other’s houses but we would be going to the college 20 minutes away, and going to frat parties, and getting accosted. And it was like, normal.”

But the message they bring to onlookers through their work is fundamentally uplifting. In fact, Greer hopes that their installation’s embrace of both the beautiful and painful parts of identity will encourage people to be kinder to each other— even when society tells us not to.

Inspiration for queer art also stems from necessity. For many LGBTQ+ people, particularly those without affirming resources and support, the pandemic has severed a vital connection to community. But artistic expression has opened the door to new and creative ways to find it.

Foster recalls the difficulty of adjusting to these new methods when the pandemic first hit. “[The internet] was one of the only places that many of us had to go, especially many queer people who want to, need to, express their sexuality in some kind of way or have some kind of sexual intimacy,” he says.

Camming in particular gives marginalized populations an extra layer of security, allowing them the same level of freedom the general public has to safely explore sexuality. A wide array of this exploration, from photos and drawings to materials and videos, is all on display in the world Foster has created in his installation. At a certain point, Foster began taking pictures of the public rooms in which webcamming took place— but without the models in frame.

Photo courtesy of Jake Foster.

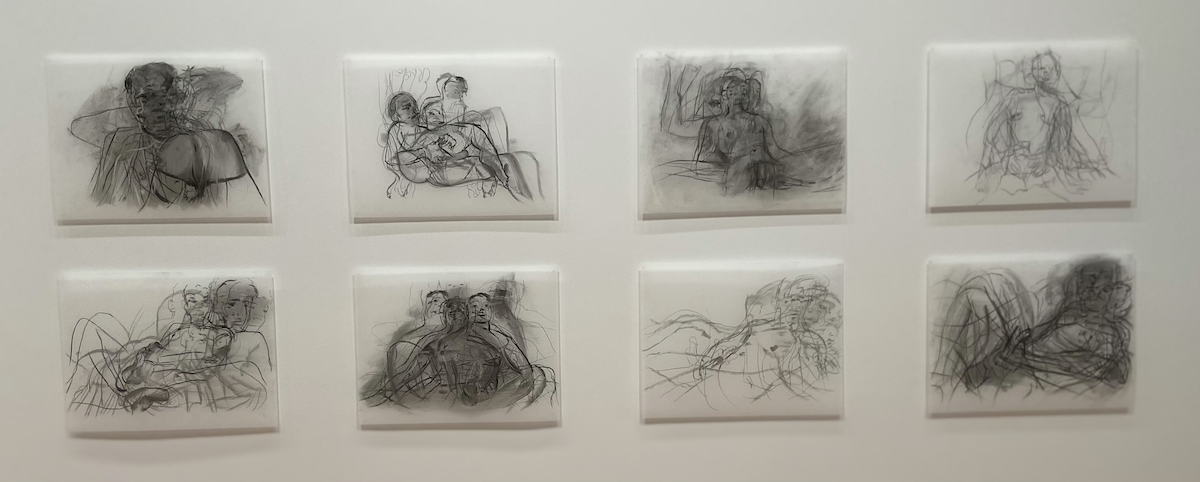

“At first, it wasn’t art for me I was just like reference because I was so interested in these rooms and how people were setting them up,” he says. But he realized that what he was really making were queer “counterarchives.” Over 900 photos of these rooms (with the additions of fluidlike model sketches) are given life in movement, performance, and interaction, both in-person and virtual.

Photo by Claire Katz-Mariani.

Greer views the interaction of museum-goers with their installation as essential. “If we weren’t in this room, there would be a plaque that says, ‘Please touch everything,’” Greer says. “‘Lay on my rug. Look up.’”

Even without the presence of other humans, Greer’s installation room feels full. The presence of community is embedded into the fabric of each piece. That companionship can be lifesaving, particularly in the face of discrimination and trauma.

Greer reflects on the deceptively unassuming pillar they repurposed with floral wallpaper from an old fraternity house.

Photo by Claire Katz-Mariani.

“It’s 2021. We’re still getting emails. Someone just got beat up two weeks ago in a frat house,” Greer recalls as we look at a pillar they have redecorated with floral wallpaper (after taking it from an old fraternity house on campus).

“Did you get that email from the cops?” they ask. (I did.) “It’s like, ‘Oh, most people get raped by people they know and just so you know you can call us.’ Call you?” they scoff. “You’re the rapists too.”

The pillar reflects our own associations with queerphobia as well. “I can tell you something, but I want to know what it does to you,” Greer explains. “Art has the power to move people’s hearts, to change people’s perceptions. I don’t think I have that power. I think the art has that power. I just get to be the vehicle.”

The revelatory honesty of these installations is both impressive and emotionally breathtaking. They reveal the irreplicable value in cobbling together our little lives and sharing that vulnerability with one another. Foster details the way imperfections enrich the art he has worked so hard to make beautiful.

There’s so much pleasure and setting up these rooms… And queer people, we fight against the regulatory regime of pleasure that hetero cis culture kind of tries to put on us. But in this digital webcam world, that regime of pleasure is unleashed so that there’s so much possibility to have fun.

Photo courtesy of Jake Foster.

“[Camming is] fraught with many problems. There’s still the system of capitalism that exists, and there’s still systems of racism,” he explains. “But I still find something beautiful and just this technosexual interaction of like, seeing someone online, and having sexual intimacy with them. And they could be miles and miles away.”

“And it’s not something to be afraid of or to be ashamed of,” he adds. “It can be really empowering and a beautiful thing. And that’s why I want to present it as something that isn’t perfect. It’s fraught with all kinds of complications, but can also be beautiful.”

Greer embodies those complications in the form of what they refer to as “slip slop, drip drop”. They have coined their own word, which headlines the installation, to describe them as well: “dykesthetics”.

“I see dykesthetics as a swath, or a covering, or a way of trying to make something that’s so fucked up just a little bit beautiful, so that maybe in that you’ll see something differently,” they say.

“As a queer person, I see the slop in everything. I see the slime in everything. Nothing is rigid, all things are fluid, and if it is rigid, it’s glitched.” They gesture to the fabric draped unevenly over the walls. “Everything’s a little bit askew. Everything’s a little bit off, even the wallpaper.”

Photo by Claire Katz-Mariani.

Clay eggs and wax amoebas are strewn about Greer’s installation, taking a multitude of imperfect shapes; some of the wax has been formed into candles and some are already dripping puddles, each one unique and captivating in its own way.

The floor and walls are also covered in the solidified clay remnants of donated underwear. Greer encourages me to walk around and touch them when I visit. I’m predictably gentle; probably too much so.

“I dipped the underwear. I put them on a clothesline. And I shoved the undercarriage or the crotch with paper or yarn or something, and then I’ve fired in the kiln, and the paper burns away the underwear… It’s a ghost and now that’s what’s left is the shell.”

I rub the shorts material between my fingers. “Clay is a wild thing,” Greer adds, “because clay is taking minerals and making artifacts. It’s turning Earth to stone. So it’s magic. It’s also trans as fuck.”

The material looks so fluid, yet feels solid and unyielding. Very trans, indeed.

As is inherently fluid nature of queerness, these temporary installations offer an infinite array of emotions and experiences for viewers and creators alike to reflect on and grow from. Foster notes that the process of creating his installation has taught him lessons he didn’t even know he needed to learn—or in some cases, unlearn.

“I realized that there was a lot about sex work and sex workers that I needed to unlearn, even though I had done it myself,” he says. “There’s so much stigma attached to sex work that I just needed to expose myself to people that were thinking differently.”

In other cases, the process of creating queer art acts as a psycologically generative catharsis.

“As a queer in the cornhole who misses the beautiful vibrant community that was my community in Chicago, I think that this is all a love letter in some ways to them,” Greer says of ‘Dykesthetics.’ “We’re the slime wads, we’re the eggs, we’re the candles.”

Photo by Claire Katz-Mariani.

While the artists definitely do the heavy lifting, we as the audience also serve a crucial role in this exhibition. There is nothing like the vulnerability you feel standing alone in an empty museum. You are left to the whims of your own psyche as it intertwines itself with someone else’s. To let that experience guide and challenge you in ways you cannot possibly predict takes strength, and necessitates empathy. But eventually, this journey is an distinctly queer way of reclaiming control over our own identities and finding solidarity in our communities. These artists have done their part to make all of this happen. Until April 24th, you have the chance to do yours.

Illinois Art+Design MFA Exhibition

Krannert Art Museum

500 E Peabody Ave, Champaign

April 3rd through 24th

Reserve your visit time here.