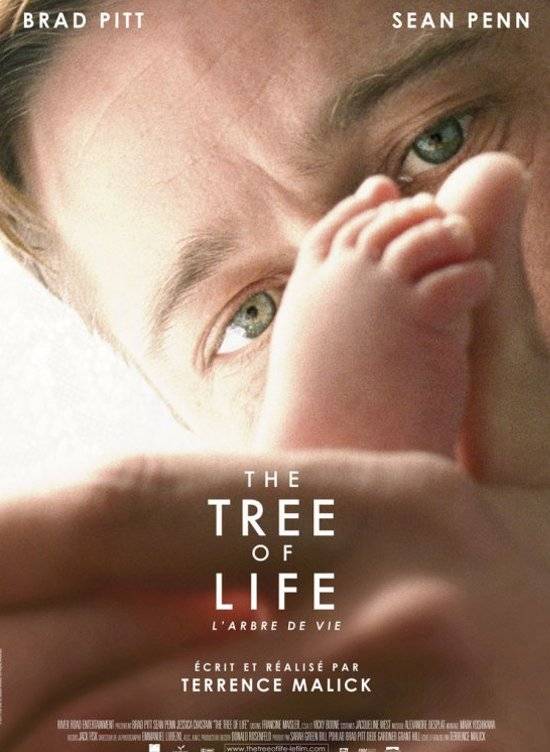

Befuddled, or maybe bored, by The Tree of Life?

People can be reluctant to describe or explain Terrence Malick’s cosmic non-action movie, understandably so. They may evade the question “did you like it?” or “what’s it about” by advising the questioner to go see it, which is really the only sound advice one can give about a movie that doesn’t lend itself to the earthbound rating systems.

It is rare to find a movie that focuses on the workings of the universe, the contemplation of illness and mortality, the mystery of family ties, the puzzles of innocence, the distance of wisdom, the parallel paragons of nature and civilization, or that refuses to tell an easy story or tug emotions along predictable lines.

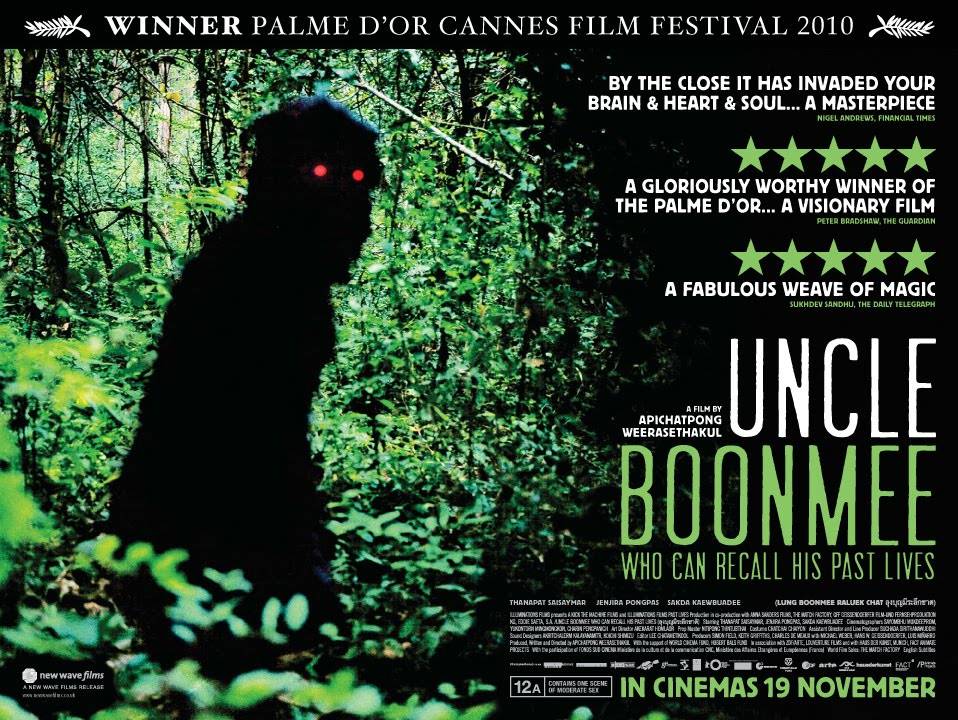

But, actually, the movie I’m describing above is not The Tree of Life at all, but another film that won the Cannes Festival Palme d’Or one year earlier. Apichatpong Weerasethkul’s Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives took Cannes’ top prize in 2010, while The Tree of Life received it in 2011. Uncle Boonmee has only this past week become available on DVD and Blu-Ray. (Don’t expect to find it at your neighborhood Redbox any time soon though.)

But, actually, the movie I’m describing above is not The Tree of Life at all, but another film that won the Cannes Festival Palme d’Or one year earlier. Apichatpong Weerasethkul’s Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives took Cannes’ top prize in 2010, while The Tree of Life received it in 2011. Uncle Boonmee has only this past week become available on DVD and Blu-Ray. (Don’t expect to find it at your neighborhood Redbox any time soon though.)

One critic said Uncle Boonmee was the Buddhist counterpart to the Christian cosmology of The Tree of Life.

Apichatpong is a relatively young Thai artist who studied at the School of the Art Institute in Chicago (where he was known as Joe, to the immense gratitude of his compatriots). He currently has a seven-screen art instillation exhibit in New York called “Primitive” that centers around his familiar themes — Thai culture, spirituality — of which Uncle Boonmee would fit in as a clear component.

One can attempt to summarize Apichatpong’s movies, but they are even stranger than The Tree of Life. Some things are certain about all Apichatpong’s films: they can stun you with natural beauty and often contain references to death, medicine (both his parents were physicians), young easy-going soldiers, animals who may speak, his country’s historical mythology as well as the equally strange contemporary Thai culture.

His films have a pervasive innocence and openness, a softness of speech and action. Characters may ride city scooters on congested streets in one scene, followed by jungle inhabitants in loin cloths in the next. Two men go to the movies and play footsie and giggle or kiss each other’s fingers. Grinning soldiers go for a ride in jeeps, gazing at the mountains as the landscape glides by. Buddhist monks visit the dentist and try to cop extra medicine without a prescription. The dead return and give advice. Family and friends sing karaoke or dance in group exercise classes on urban plazas. People seem to take a lot of picnics.

Blissfully Yours (2002) begins in a medical office where a mute young man, flanked by two women, receives treatment for a skin rash. The women try to cure him with home remedies. They go for an extended picnic in a spectacularly beautiful forest/jungle. The younger woman and man slip into the river and engage in innocent (yet explicit) intimacy, the likes of which you would never see in an American movie. The other woman chases bugs off the picnic food. The end.

In Uncle Boonmee, an ox escapes from his tether in the moonlight. Glowing-eyed ghosts appear in the forest. Family members gather around the dinner table as Boonmee speaks openly about his terminal illness. His dead wife appears and everyone tells her how young she looks. His dead son, Boonsong, also joins the group. His body is covered with long hair. A story is told (shown) about a princess who makes love to a feisty catfish in the river. After the funeral, a young Buddhist monk in saffron robes visits two women in a room and they watch television. The monk strips to his boxers and takes a shower. The woman goes to a noisy neon restaurant. She is alone. The end.

But, of course, these are valid descriptions only if you think movies can be summarized in a 30-second pitch to executives or follow the typical narrative arc we have come not only to expect but demand. It would probably be a much easier job describing the fifth Pirates of the Caribbean, the third Transformers, the eighth Harry Potter, or the second Hangover, none of which I’ve yet had the time or endurance to catch.

I’m going to stick my neck out here and say both The Tree of Life and Uncle Boonmee each offer up a singular vision of transcendence, an extreme meditation that forces you to see things in a new way, if you have the willingness to be open to their parallel universes.

I’m going to stick my neck out here and say both The Tree of Life and Uncle Boonmee each offer up a singular vision of transcendence, an extreme meditation that forces you to see things in a new way, if you have the willingness to be open to their parallel universes.

In 1968, I took my religious-minded father to see Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. His entire (and negative) synopsis was that the movie “implied reincarnation.” His take on Malick’s The Tree of Life would probably be that it “implies evolution.” I don’t even want to imagine what he would think about Uncle Boonmee, where reincarnation and human/animals aren’t implied; they’re explicit.

The father/son relationship is important in Uncle Boonmee, but in The Tree of Life paternalism is one important key to interpreting the movie at all. Brad Pitt’s father is both cruel and kind, trying hard to be successful in a world that seems beyond meaning or understanding, and failing, heartbreakingly.

Many people fault The Tree of Life for seeming to show a universe without meaning. I don’t think that’s the case. If anything, Malick seems to be showing us a world that is unknowable, but not meaningless. The whispering narrator speaks of two ways of dividing up the world, the way of nature (depicted by the father) and the way of grace (the mother).

All Malick movies have poetic voice-over narration. The line that stuck with me in The Tree of Life was that time is fleeting if one doesn’t love. Was that true? The mysteries of time and love. The first word in the movie is “brother.” The second is “mother.” I had to wonder. Do I love? Enough? At all?

Some have called The Tree of Life pretentious, as though it offered answers to deep questions. Again, I didn’t read it that way. It doesn’t have the answers. Like philosophy itself, it asks the questions.

Technically, both The Tree of Life and Uncle Boonmee are well-composed, artistic achievements, frame-by-frame, cut-by-cut compositions worthy of watching sheerly for the visual pleasure of it.

Both movies also criticize contemporary urban life visually, in The Tree of Life the grown child (portrayed by Sean Penn) sulks in his angular, high rise cityscape, and Uncle Boonmee concludes in a garish karaoke bar as soft music plays in a blinking neon confusion.

If one wanted to quibble, The Tree of Life may be more visual than meditative, while Uncle Boonmee is more meditative than linear or narrative. The Tree of Life shows life progressing right from the birth of the universe; in Uncle Boonmee, life and time are circular.

A major difference is that The Tree of Life lacks humor, a real flaw, while Boonmee (and all of Apitchatpong’s movies) makes room for giggling, even at the most serious subjects.

While The Tree of Life uses a background soundtrack of swelling classical Western music, Uncle Boonmee‘s soundtrack is almost entirely composed of the incessant chirping of crickets, the droning of bees where Uncle Boonmee cultivates tamarind honey, the splashing of waterfall cascades, and then at Boonmee’s funeral, the chanting of Buddhist monks, all these sounds the same and endless, the universe blended into one continuous buzz.

Both The Tree of Life and Uncle Boonmee are beautiful soul food, experiences to be seen and experienced. Don’t bring any expectations. If you don’t have time to meditate along with these two directors, you’re better off doing something else.

If you do see them and think you are prepared, nevertheless you may find yourself waiting for something to happen, only to realize by the end credits that it had been happening all the time you were waiting, continuous with surprise and pain and joy and wonder, just like life.

——–

The Five Features of Apichatpong Weerasethkul

- Mysterious Object at Noon (2000)

- Blissfully Yours (2002)

- Tropical Malady (2004)

- Syndromes and a Century (2006)

- Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (2010)

The Five Features of Terrence Malick

- Badlands (1973)

- Days of Heaven (1978)

- The Thin Red Line (1998)

- The New World (2005)

- The Tree of Life (2011)

(All films available at That’s Rentertainment, with the exception of The Tree of Life, which ends its run at the Art Theater this week)