There is something very magical and special about playing music with someone you know very well and love like a family member or a significant other.

— Megan Johns

There are many multi-generational families making music, both together and separately, in Champaign-Urbana, from Tom and Matt Turino, who collaborate in any number of string-band ensembles, to Stephen Swords, who played a keyboard line on his son Shannon’s hip-hop album.

There are many multi-generational families making music, both together and separately, in Champaign-Urbana, from Tom and Matt Turino, who collaborate in any number of string-band ensembles, to Stephen Swords, who played a keyboard line on his son Shannon’s hip-hop album.

And then there are families whose musical history stretches back before World War II, like that of Megan Johns, who plays solo and in Moonwish. Johns’ mother, Kristen, has produced several albums with Pogo Studios’ Mark Rubel and is still active in the C-U Symphony, and Megan’s grandparents (Kristen’s parents, Helen Reynolds and Robert Waddell) played in a jazz band that entertained audiences from the roof of the Robeson Building and other local venues in 1940 and 1941.

On the rock side of the ledger, there’s Andrew Pritchard, the drummer in Enta, and his father, Mike, who has been in C-U bands for decades, including Rathskeller, Mike Roberts, The Unpossible, and the Gavin Stolte Project. And former school music teacher Joe Wachtel and his wife, Lori, have a brood of up-and-coming musicians; their adolescent sons, Joey and Dan, are in Birds and Snakes and Aeroplanes, as well as Rusty Scones.

From a global perspective, Patience Mudeka, who emigrated to the U.S. at age seven- teen from Zimbabwe, inherited her love of music from her grandparents, and she is now passing along that love to her seven-year-old son.

Tom and Matt Turino

The Turinos are one of our best-known local, musical families, and for good reason: they’ve been playing together ever since Matt (who’s now the assistant manager at the Sustainable Student Farm) was a nine-year-old fiddle player. Tom, who’s a recently-retired University of Illinois professor of ethnomusicology, used an early gig at the Urbana Farmer’s Market as a motivational tool. “[Matt] didn’t get much support from his pals for the kind of music we were playing,” Tom recalled. “He was stopping practic- ing at that time. I think he was maybe losing interest.” Matt concurred:

There were definitely times when I was frustrated with having to practice. None of my friends really did music at all, and I felt like it was this weird other thing that I did outside of what my friends were doing.

So, the duo, with Tom on Cajun accordion, put out their case at the Market:

There weren’t very many other people playing back then—I don’t think anybody else was playing—and he was a cute ten-year-old playing the fiddle, and the money came pouring into the case for the cute factor. So we got home, and I said, “Well, you can keep all that money.”

And what was Matt’s reaction? “He said, ‘Dad, we gotta do that again!’ So, I said, ‘OK, if we’re going to be playing out, we’ve got to practice more.’”

Their musical bond has only grown stronger over the years. Tom stated, “We’re in a bunch of different bands together, and sometimes people can’t show up, but I always say, ‘As long as Matt and I are both there, it’ll be OK.’” Matt said, “When I play with my dad, we have a very focused and cohesive aesthetic sense in a lot of ways.” Tom continued, “When we play together, it’s a unit that’s so tight, it’s a joy.”

Matt thinks that their participatory model is a good one to emulate: “I would highly encourage anyone who plays music, if they have kids, do it with their kids, and make it an activity [together] rather than something you go off and practice.”

Kristen and Megan Johns

As stated earlier, Kristen and Megan’s local musical roots go back at least one addi- tional generation. Megan recalls a childhood filled with music: “Music was everywhere always and pretty much colors all my memories.” She continued, “I don’t know what would have happened if I had not been encouraged and educated in creative pursuits from the beginning.”

Megan stressed that playing music with family members has been a huge influence on her as a musician. “It seems easier to coordinate and move intuitively through music without the introductions,” she said. “More immediate. Disagreements can also be worked out faster I think—or they can take longer, depending on the family member.”

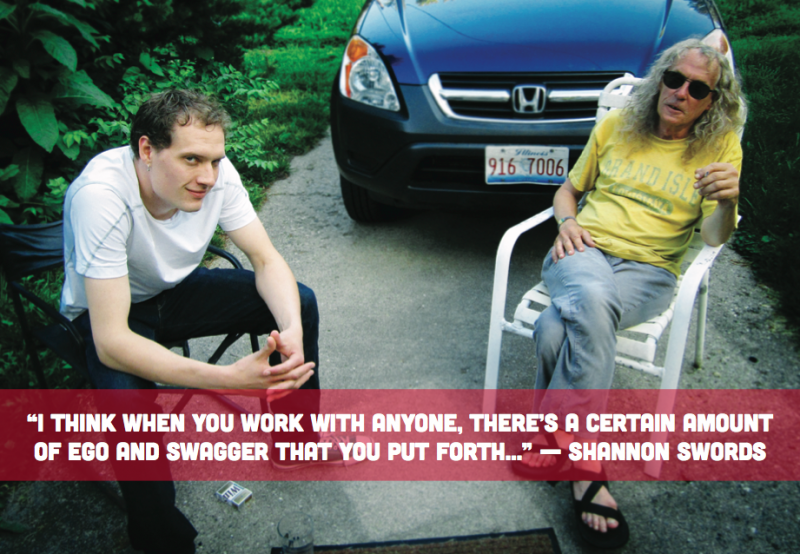

Stephen and Shannon Swords

On the surface, two generations of Swords may not have much in common musically with each other, but their familial bond shines through their differences. Shannon performs hip-hop under the moniker Swords, while his father, Stephen, had a more straightforward rock and soul background, playing guitar and keyboards in several Charleston, Illinois, bands in the seventies, eighties, and nineties. “I started playing rock music really poorly when I was fourteen or so,” Shannon explained, “and I started getting into hip-hop when I was seventeen. That was my differentiation of myself from my pop.”

Stephen contributed a Fender Rhodes keyboard line to the first track on his son Shannon’s recently-released hip-hop album, Depth:

I had a framework for a song. I had a sampled guitar part, a drum line, a bass line, and some rhymes written. My apartment was actually getting cleaned at the time, and so I was staying (at my parents’ house); this is where the studio is. I was like, “This is the song,” and Padre was like, “Do you have a Fender Rhodes on your keyboard?” I said, “Yeah.” He was like, “Can you make it dirtier?” So I added some distortion and we got the first track for the album with me sitting next to him rhyming so he’d know what the vocals would sound like.

The woozy keyboard meshes perfectly with Swords’ percussive vocals.

On working with his father, Shannon said, “I think when you work with anyone, there’s a certain amount of ego and swagger that you put forth, and at the end of the day, we can’t really break up as a musical unit.”

Stephen concurred, “It’s his project, and that is fundamental to me. Whether it’s right or wrong, he’s going to make it into what he wants to make it into.”

Patience Mudeka

Growing up in Zimbabwe, Patience Mudeka was raised by her grandparents, and played music with her cousins and aunts and uncles:

Playing music with family members makes the music gel together a lot better; the music feels a lot more connected. In a sense, each family has its own secret language, little signs, and certain eye contact, nonverbal and verbal communica- tion. When I play music with my family we use a lot of nonverbal communication to cue ourselves for certain changes in our music.

Mudeka has a cousin and an aunt who are professional musicians in Europe, although they didn’t have a formal music education: “Other than my kids, no one else in the family can read sheet music. We all learned music by ear.” She’s passing along her love of music to her children, including her seven-year-old son. “A couple of days ago, I purchased a First Act drum set for my son who is seven and loves music,” she said. “He goes from rapping, singing, a little piano, and now drums.”

Mike and Andrew Pritchard

Andrew Pritchard has strong memories of his father’s musical influence, but he didn’t directly follow in his footsteps:

My dad had a huge vinyl/CD collection, so I remember plugging in the head- phones with some fruit snacks and listening to the latest from Rush or Scorpions. My dad had a spare guitar that he would let me strum on, and we’d mess around in the living room together some days. However, it became clear that rather than actually learn how to play an instrument like the guitar, I was better off just mak- ing noise banging on the drums.

Having a father with an extensive live performance background also strongly affected Andrew:

I’d set up my own concerts in the garage with a boom box and a broom with a rope tied around it for a guitar. Then I eventually made some friends who were in bands themselves and worked my way into their group.

Joe, Joey, Dan, and Lori Wachtel

Joe Wachtel, who recently completed his doctorate, has a slightly more academic take on the question of musical succession. For instance, he often found that his sons, Joey and Dan, actually learned more from their own musical explorations than from the lessons he tried to directly impart to them. “I always tried to teach both of my sons how to play instruments from an early age, both in the classroom and at home, to the usual mixed success one would expect when a parent attempts to teach their child,” Joe explained.

But Joe had to live apart from his family when he first started grad school, and he was surprised to find that his children didn’t necessarily need his direct instruction:

As I reflected on my struggles to teach them to play these instruments in the past, I marveled at their ability to learn on their own. More meaningful musical encounters with my children began to occur. The forced classroom encounters and home lessons became mutual and cooperative jam sessions. When they started playing, I went to the room and joined in instead of correcting and teaching. I listened to what they were doing and played off what they knew, rather than try to tell them what they should do.

Joey added, “Playing with Dan is nice because we know each other’s strengths and weaknesses. Also, there’s a certain tension when working with other people, since I don’t know about their style of playing.” Dan noted that he is asked to be quiet in class a lot because he likes to talk about Scandinavian Metal.

Photo by Celine Broussard, Sean O’Connor, and Joel Gillespie.

This story was originally published in Bonfire, the print companion to Smile Politely. The Autumn/Winter 2013 edition was published and distributed around Champaign-Urbana at the end of August 2013. Over the next several months, we will publish the stories featured in Bonfire on Smile Politely.