is for Insect. You may not think that February is the most likely time to find these critters out and about, but rest assured. We’re coming up on one of the best reasons to live in Champaign-Urbana in this grey and tedious month. Take out your calendar: on February 28th you won’t want to miss the 32nd annual Insect Fear Film Festival.

is for Insect. You may not think that February is the most likely time to find these critters out and about, but rest assured. We’re coming up on one of the best reasons to live in Champaign-Urbana in this grey and tedious month. Take out your calendar: on February 28th you won’t want to miss the 32nd annual Insect Fear Film Festival.

You’re in for a unique treat. Head over to Foellinger Auditorium on the U of I quad at 6 for an up-close-and-personal introduction to this year’s petting zoo. Ever wanted to know what those fuzzy black tarantulas feel like? Or see a blue death feigning beetle in action? Join your fellow fans to admire a favorite — the warty glow spot cockroach. The Entomology Graduate Student Association is, as I write, assembling their favorite specimens to make this a once-in-a-lifetime experience. And at 7 p.m. it gets even better — this year’s films feature female entomologists. Check them out. Nightmare on Locust Lane, The Case of the Mysterious Moth, or the bloodthirsty suspense of Mansquito.

You’re in for a unique treat. Head over to Foellinger Auditorium on the U of I quad at 6 for an up-close-and-personal introduction to this year’s petting zoo. Ever wanted to know what those fuzzy black tarantulas feel like? Or see a blue death feigning beetle in action? Join your fellow fans to admire a favorite — the warty glow spot cockroach. The Entomology Graduate Student Association is, as I write, assembling their favorite specimens to make this a once-in-a-lifetime experience. And at 7 p.m. it gets even better — this year’s films feature female entomologists. Check them out. Nightmare on Locust Lane, The Case of the Mysterious Moth, or the bloodthirsty suspense of Mansquito.

There’s a reason why it’s called the Insect Fear Film Festival. We may as well look straight in the eye at some peoples’ feelings. I’m sure there are those of you who truly fear, detest, loathe — do you have a more accurate word? — the little mysterious noisy pesky creepy sometimes stinging or chomping beings I’m championing. You have good company.

There’s a classic article written by psychologist James Hillman, Why We Hate Bugs. Here’s the official analysis:

- there are so MANY of them (yup, something like 200 million for every single human)

- monstrosity — as in weird, ugly, grotesque, no need to even use your imagination

- they invade our space with no warning — picnics, kitchens, beds, eeks!

- they’re mysterious — cold blooded, no feelings, so many legs. And even more bizarre under a microscope…

Let me encourage a different perspective.

This community is rich in people who spend their days looking closely at insects, from the ones most people avoid — say, cockroaches, wasps, or mosquitoes — to the more amicable cicadas, butterflies, moths, flies, dragonflies, ants, honeybees and more. In some hidden pocket of Champaign-Urbana someone can give you a good reason to appreciate their particular favorite. And we have more than our share of official researchers dedicated to dealing with pests — from basic annoyances to disease-carriers, invaders, and crop-killers.

It would be a mistake to think that because they’re small, insects don’t deserve our attention. For one thing, they outweigh people ten to one. Humans have been around for some three million years – insects for 300. And more than half of all known living organisms are insects – we’ve identified one million species so far, and scientists guess there are 5-6 million more.

The word insect itself means “cut into segments.” At one point in its lifespan, every one has three body parts — head, thorax and abdomen — and six legs. It may hatch out of the egg looking like a miniature adult, or it may morph from a caterpillar or grub to pupa or chrysalis. For convenience, the entomology department also studies spiders, which are officially arachnids, not insects. But if you’re heading for the petting zoo, I wouldn’t hold an extra two legs against them.

What about “bugs”? To be precise, these fall in just one order of insects, Hemiptera or “half wings.” The inscrutable late-summer drone here is the product of a healthy bug population — specifically cicadas.

The best place to check out the science side is Morrill Hall on Goodwin in Urbana. Our entomology department has a rare spirit, beginning with its chair. May Berenbaum is no everyday professor. What other person on campus has an X-files character named after her? And just this fall she was welcomed at the White House by President Obama to receive the National Medal of Science for “pioneering studies on chemical coevolution and the genetic basis of insect-plant interaction, and for enthusiastic commitment to public engagement that inspires others about the wonders of science.” Enthusiasm and inspiration only begin to describe her impact on local, and indeed global, understanding of insects.

Loud and clear on the department website is an invitation to share the excitement. I followed the outreach link and received a warm welcome from Tyler Hedlund, who coordinates a wide range of activities with co-chair Katie Dana. Their schedule includes science fairs and demonstrations, the IFFF (insiders know that’s the film festival), National Pollinator Week, and off-the-cuff tours to random visitors like me.

Hedlund studies the black legged tick and Lyme disease in the Chicago area, but he’s also an enthusiast for insects as pets and good company. He recommends cockroaches in particular; who else would say they’re “cute and charismatic”? You can see him here with an affectionate eastern lubber grasshopper, popular among the live residents of the Morrill Hall insectary. Don’t miss Tyler at the petting zoo on February 28th. He’s also available on the Entomology hotline to answer any questions you might have — the harder the better.

Hedlund studies the black legged tick and Lyme disease in the Chicago area, but he’s also an enthusiast for insects as pets and good company. He recommends cockroaches in particular; who else would say they’re “cute and charismatic”? You can see him here with an affectionate eastern lubber grasshopper, popular among the live residents of the Morrill Hall insectary. Don’t miss Tyler at the petting zoo on February 28th. He’s also available on the Entomology hotline to answer any questions you might have — the harder the better.

One notable adventure among outreach activities is “entomophagy” — that’s anything to do with eating insects. They are normal table fare everywhere except the western world, valued for high protein and interesting textures. Deep fried cicadas are a specialty in China. And don’t stop there, particularly during the next 17-year swarm. How about pizza? tacos? Even jello! If that’s a bit much, you don’t have to tackle six legs and all those antennae to enjoy a rich food source. Hedlund stocks cricket flour and finds it makes tasty cookies.

I was intrigued by another outreach topic, bioinspiration. The practice lives up to the word: finding ways to apply animal characteristics and behavior to human innovations. An advanced digital camera design from John Rogers’ material science lab on campus came out of studies of the compound insect eye. Prof. Marianne Alleyne teaches the essential course on bioinspiration, and shares projects on her blog, Insects Did It First. Her lab is engaged in a number of collaborations with other departments, including engineering, architecture and business. A hot topic among architects is “adaptive biomimetic building envelopes,” which explore how the outside of a building could mimic the abilities of insects to manage body temperature, water balance, and to sense their surroundings. With some 290 million more years’ experience on earth than humans, insects should provide some tips on how to adapt.

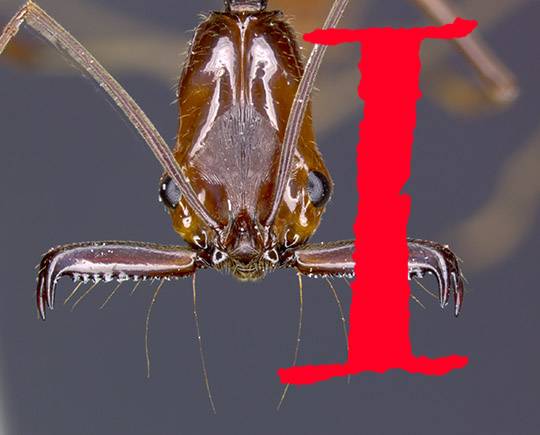

The mechanics of insect movements are compelling as well. Thanks to the UI Beckman Institute’s high speed photography set-up, grad student Josh Gibson is taking a micro look at the trapping mechanism of ant mandibles. There is one species that seizes prey so fast that it has been measured as the second fastest movement known in the animal world (and in case you want to know the absolute fastest, Josh tells me it’s a certain jellyfish stinging mechanism). Admire the jaw of Odontomachus hestatus, in Josh’s photograph at the beginning of this article. He and lab partner Nadia Espirito Santo, visiting from Brazil where the ants are native, take full advantage of the lab directed by Scott Robinson, expert in the many kinds of microscopy.

Robinson helped develop and hosts another singular outreach activity of the university: Bugscope. Students anywhere in the world are invited at no cost to submit their own specimens which Scott then prepares for a state-of-the-art electron microscope in the basement of Beckman. And via basic Internet connection, the class can see their bugs in real time at nanoscale – that’s smaller than the wavelength of light. The students in Oprah Winfrey’s Leadership Academy for Girls in South Africa have peered into the microscope in Robinson’s lab thanks to Bugscope.

Robinson helped develop and hosts another singular outreach activity of the university: Bugscope. Students anywhere in the world are invited at no cost to submit their own specimens which Scott then prepares for a state-of-the-art electron microscope in the basement of Beckman. And via basic Internet connection, the class can see their bugs in real time at nanoscale – that’s smaller than the wavelength of light. The students in Oprah Winfrey’s Leadership Academy for Girls in South Africa have peered into the microscope in Robinson’s lab thanks to Bugscope.

He is dedicated to enticing students toward science as a way of life. After fifteen years of sharing the wonders of Bugscope, he’s found that insects are the perfect bait because they look spectacular at different scales. Scott will be showcasing the “coolest grossest things” he can show on the electron microscope, for your delight at the Film Festival — take advantage of it!

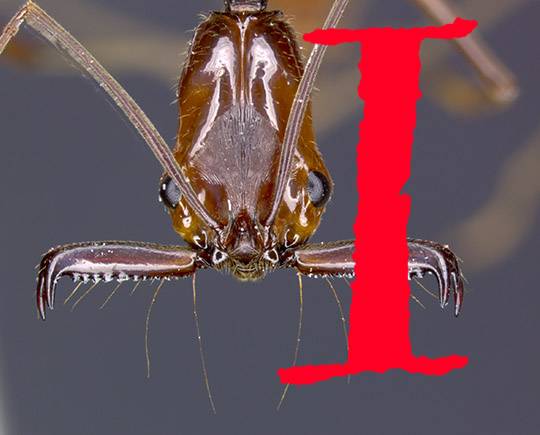

May Berenbaum and Prof. Gene Robinson are behind another local entomology resource to be celebrated. Have you ever pondered the wonders of pollination? One-third of all the food we eat depends on it — without insects, we’d starve. Any Saturday or Sunday between 1 and 4 pm, turn onto the dirt road off Windsor just east of Lincoln and head toward the vivid blue-muraled building (courtesy of local artist Glen Davies) and visit the Pollinatarium — this country’s first-ever freestanding science center devoted to pollination. You’re likely to be met by Leslie Deem, impresario; she’ll be delighted to give you the full tour.

Check out the beekeeper fashions and the live hive — queen and worker bees at home for you to admire. The delightful displays are by the Illinois Natural History Survey team. You can even register to be an official Beespotter and be trained as a “citizen scientist” on the team that logs bee sightings — part of the effort to understand and counteract the serious threats to bee populations.

Every second grader in Champaign gets a tour. Leslie will gladly put you on her calendar, along with school groups, girl scouts, 4-H’ers and more. And it will be a full-scale party out there from June 15-21, National Pollinator Week.

Not everyone focusing on insects in town is cheerleading. Corn flea beetles, emerald ash borers, Asian longhorned beetles — there are some serious challenges to crops, forests, gardens and the balance of nature overall, and more on the horizon.

You need go no farther than the Illinois Natural History Survey to find experts on the case. Kelly Estes coordinates the Illinois Cooperative Agriculture Pest Survey, or CAPS, and is at the moment offering a series of First Detector Training Programs to anyone interested. She maintains a network of insect trapping sites at likely points of entry for potential invasions, such as highway rest stops for trucks carrying containers of lumber and produce. She puts together a wide range of educational materials, and is available to answer any questions about suspicious insect activities — such as a rise in ground-nesting wasps in ballfields across the state.

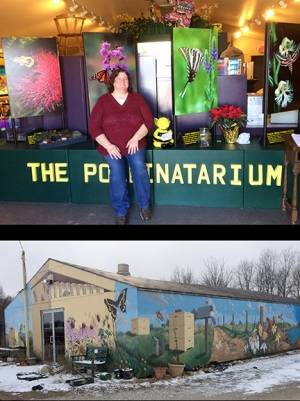

The outreach department of the Natural History Survey at 1816 South Oak puts together an array of bright and compelling displays and 3-dimensional models to teach the wonders of insect life, including the one shown above from the Pollinatarium. I had a delightful tour of their working studio from Patty Dickerson, who devises ingenious ways to build all kinds of models. She molds in plastic, sews, saws, paints, haunts local crafting stores — whatever it takes to bring these creatures to life.

The outreach department of the Natural History Survey at 1816 South Oak puts together an array of bright and compelling displays and 3-dimensional models to teach the wonders of insect life, including the one shown above from the Pollinatarium. I had a delightful tour of their working studio from Patty Dickerson, who devises ingenious ways to build all kinds of models. She molds in plastic, sews, saws, paints, haunts local crafting stores — whatever it takes to bring these creatures to life.

I was fascinated by this intriguing bit of construction: an oversize model of segments connected to a gear with a hand crank to demonstrate just how a caterpillar moves all those legs.

And so what about Insects and Art? I posed just this question to the Krannert Art Museum’s Giertz Education Center and was pleased to meet Virginia Erickson, who has her finger on the pulsepoint of the collections. She led me immediately to three handsome pieces.

And so what about Insects and Art? I posed just this question to the Krannert Art Museum’s Giertz Education Center and was pleased to meet Virginia Erickson, who has her finger on the pulsepoint of the collections. She led me immediately to three handsome pieces.

The Egyptians portrayed the rising sun as an orb pushed by a beetle that encases its eggs in a ball of dung. Here’s the story in a 12th century BCE limestone carving of Kheperi the sun god with a classic scarab – known to us in less glory as the dung beetle.

School-age visitors particularly enjoy this 15th Century plate, made by French artisan Bernard Palissy from castings of real insects, snakes and more. How would you like your breakfast toast on that?

School-age visitors particularly enjoy this 15th Century plate, made by French artisan Bernard Palissy from castings of real insects, snakes and more. How would you like your breakfast toast on that?

From there we moved to a piece that shows another way insects serve human aesthetics. For centuries, weavers in central and south America have used vivid red carmine dye made from a scale insect found on cacti. Known as cochineal, this was valued second only to silver by early European traders with Mexico. The Mayas and Aztecs made good use of it; here’s a gorgeous specimen woven in Peru some 3000 years ago.

Indeed, a major impetus for trade across the globe — and even the rise and fall of civilizations — came about thanks to the simple silkworm, the caterpillar stage of the silkmoth Bombyx mori. The rich silks woven in China were so prized in the west that the Silk Road became a major trade route dating from the Han dynasty around 200 BCE, eventually spanning 4,000 miles. The profits were so important that the Chinese extended the Great Wall to protect travellers along the road. I don’t think it’s too much of a stretch to say that insects played a part in building the Great Wall of China.

The beauties of silk fascinate people in east central Illinois as well. Last year Spurlock Museum collaborated with the Champaign Urbana Spinners and Weavers Guild in a show of contemporary fiber arts created in response to works in the collection. I enjoyed a conversation with one of the artists, Esther Peregrine, who raises silkworms in shoeboxes in her living room. She feeds them mulberry leaves gathered on her way home from work, waits for the worms to spin cocoons, and performs the painstaking work of separating the fibers — from one cocoon a strand can reach the length of 12 football fields. She spins them into thread, dyes it and lets her inspiration create original Illinois silk. We can thank Esther for these photographs.

So — are you I for infatuated? Maybe just intrigued.. Check out the Smile Politely Radio podcast from February 20th for the inside story on the Insect Fear Film Festival. You can even read up on female entomologists, this year’s theme, thanks to Prof. Alleyne’s graduate students. They’re posting profiles of their favorites.

If you’d like to ponder the humanistic side, try Cultural Entomology, a journal dedicated to “the reasons, beliefs, and symbolism behind the inclusion of insects within all facets of the humanities… including art, religion, philosophy, folklore, beliefs, and literature to name a few.” Sounds like the perfect February armchair adventure to me.

———

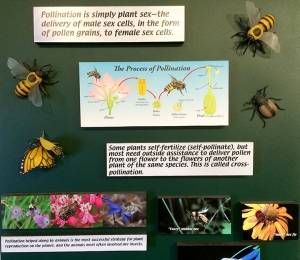

And I can’t forget a nod to the letter “i.”

In English, it’s the fifth most used letter. The earliest form we know is the Phoenician yodh, meaning hand, from 1000 BCE — the left sketch below. To its right is the more angular form the Greeks developed. Over time they simplified it to a single stroke, their “iota,” which they used as a vowel. The Romans rendered it with brush and chisel, which introduced serifs in the formal form. You can read about that here if you missed my last foray, T is for Typography.

It was in late medieval times that a dot was added — today we call it a tittle — to distinguish the single line from similar forms.

Cope Cumpston is a typographer, book designer, and community enthusiast resident in Urbana. You can reach her here.

Other letters in abecedarian C-U live here.